Everest HV-916 16Ch Görüntü H.264 4Ch Ses DVR Kayıt Cihazı - Kanal DVR Kayıt Cihazı ları sahibinden.com'da - 1102788830

Everest XVR-208HD 8 Kanal H.265 XVR Kayıt Cihazı Fiyatları, Özellikleri ve Yorumları | En Ucuzu Akakçe

Everest HV-8016 16 Kanal H.264 DVR Kayıt Cihazı Fiyatları, Özellikleri ve Yorumları | En Ucuzu Akakçe

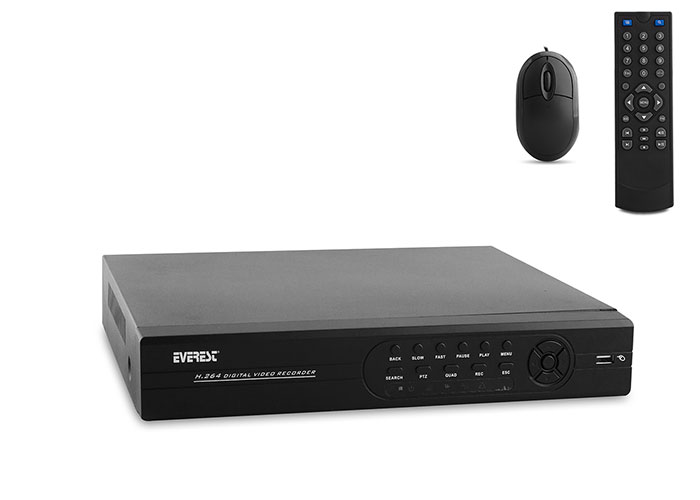

Everest HV-816H 16Ch Görüntü NVR + Analog Desteği 960H 6Ch Ses DVR Kayıt Cihazı - Bütünü Oluşturan Parçalar