Pevné Monokiny Ženy Čierne Plavky Backless Sexy Plavky Vysoký Pás dvojdielne plavky Bikiny, Leto Vintage Pláž, Kúpanie Oblek S~XXL kúpiť | Šport a zábava / www.spinkacovo.sk

Pevné Monokiny Ženy Čierne Plavky Backless Sexy Plavky Vysoký Pás dvojdielne plavky Bikiny, Leto Vintage Pláž, Kúpanie Oblek S~XXL kúpiť | Šport a zábava / www.spinkacovo.sk

2021 Klasické Čierne Plavky Leto Ženy Konzervatívny Jeden Kus Push Up Plavky Bikiny Sety Jumpsuit Swimdress Beach Party Nosenie predaj \ Dámske Oblečenie / www.metropolbar.sk

Výpredaj! Ženy jeden kus čierne plavky ženy ruched bruško kontroly plavky klasické plavky, letné beach momokini | Šport a zábava \ Zdravozit.sk

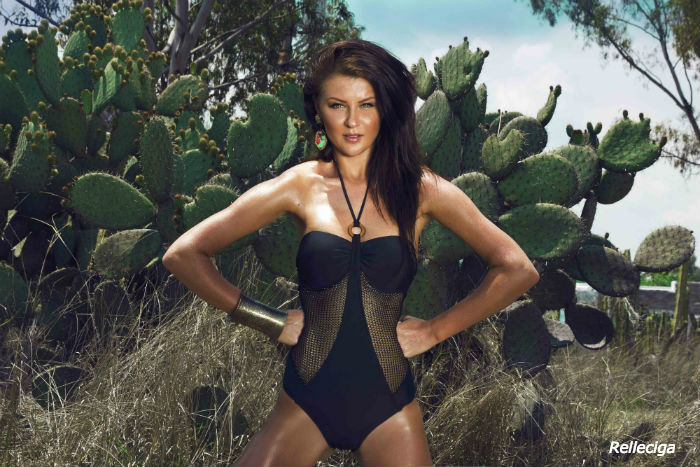

Najkrajšie plavky na leto 2015: Trojuholníky tvarujú krásne prsia, celé plavky s výstrihmi nie sú pre každú - galéria | 11 | Feminity.sk

Najkrajšie plavky na leto 2015: Trojuholníky tvarujú krásne prsia, celé plavky s výstrihmi nie sú pre každú - galéria | 12 | Feminity.sk

Pevné Monokiny Ženy Čierne Plavky Backless Sexy Plavky Vysoký Pás dvojdielne plavky Bikiny, Leto Vintage Pláž, Kúpanie Oblek S~XXL kúpiť | Šport a zábava / www.spinkacovo.sk

Plavky - dámske plavky - dvojdielne plavky - krásne jednofarebné push up plavky so zlatými pásky - push up - leto - výpredaj skladu - TIANO.SK

Výpredaj! Ženy jeden kus čierne plavky ženy ruched bruško kontroly plavky klasické plavky, letné beach momokini | Šport a zábava \ Zdravozit.sk

Výpredaj! Ženy jeden kus čierne plavky ženy ruched bruško kontroly plavky klasické plavky, letné beach momokini | Šport a zábava \ Zdravozit.sk

Dvojdielne Plavky Bikiny 2022 Nové Jednofarebné Dámske Plavky Leto Sexy Plavky ísť Na Pláž, Kvalitné Trojuholník Pohár Ohlávka \ Dámske oblečenie ~ www.ombrepizza.sk

-800x800-0-.jpg)